So we’re at the last day and wow, haven’t we just been overloaded with policies aimed at assisting women…

Sigh. Other than some (much needed) policies and small funding on domestic and family violence, policies which treated women as anything other than those who will benefit from things that the man in the household will get were few and far between.

Gender inequality remains a major problem across the Australian economy and society. The most famous measure of this inequality, the gender pay gap remains significant, though there has been slow progress.

The gender pay gap measured by average (mean) weekly cash earnings, ie how big your weekly payslip is, is 26.5%. – That means the average earnings of men is 26.5% more than women.

As soon as this is uttered people (men) will jump up and say that much of this is driven by part-time work; women are far more likely to be in part-time work than men, predominantly due to caring responsibilities such as for children and aged relatives.

And great. Well done on grasping the numbers but missing the point.

Firstly of course much more work done by women – regardless of employment situation – that is essential for society to function, it is unpaid.

Even in situation where both the man and the woman in a household work full-time, women will do more unpaid work. Heck even in situations where the woman is the main breadwinner, women are still more likely to do more unpaid work!

And all this time doing essential, but unpaid work, has a big impact on earnings.

Due to caring responsibilities, women are more likely to experience periods out of the formal workforce, where they receive low or no wages at all. There is also a significant and persistent ‘motherhood penalty’, research from the Australian Treasury showed that “women’s earnings fall by an average of 55 per cent in the first 5 years after entry into parenthood, while men’s are unchanged”.

Another commonly cited measure of the gender pay gap just looks at full-time adult earnings (excluding overtime and bonuses), under this measure the gap is 11.9%.

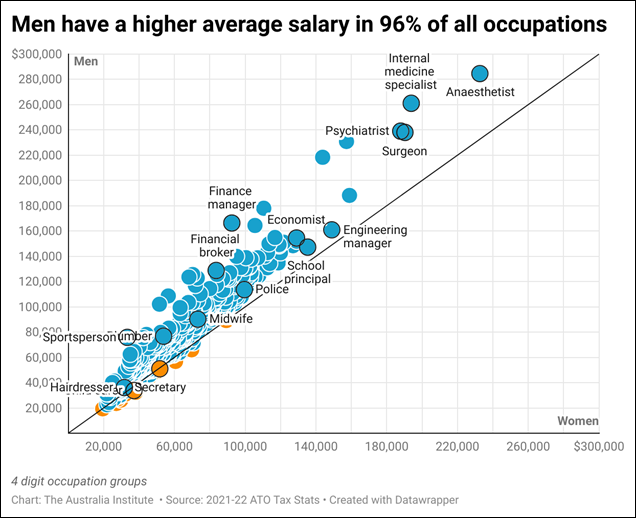

This gap is generated by various factors including that women tend to be paid less in most occupations and female-dominated industries are generally paid less. Australia Institute research shows that in 2021-22, men had a higher average salary in 96% of all occupations – including midwives!

The figures also show that higher-paid occupations are more likely to be male-dominated. Among the 77 highest-paid occupations, where the average salary was above $100,000, only 2 were jobs where women make up more than 60% of the workforce.

By contrast 40 of the 70 lowest-paid occupations, where the average salary was less than $45,000, were jobs where women make up more than 60% of the workforce. Importantly, many female-dominated industries are in the public sector or largely government funded, meaning that the government could easily boost these wages if it chose to.

These differences add up over time, contributing to substantial wealth differences between men and women. Additionally, as Australia’s superannuation system ties retirement with lifetime wage earnings we see the gender wage gap mirrored in retirement. The average super balance for 60 to 64-year-olds in June 2021 was $402,838 for men and $318,203 for women – a gap of 21.0%.

So was any of this a focus in the election? No. Not really. The closest we got was the fight over work from home, which has been one of the few policies of the past decade that has truly helped women stay in work while also caring for children or elderly/sick relatives.

But much more needs to be done – including at the societal level to make unpaid care work much less of a women-dominated responsibility.

No comments yet

Be the first to comment on this post.